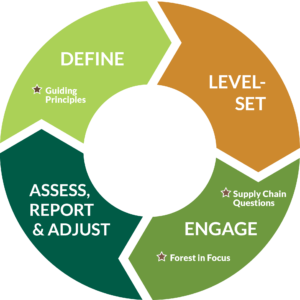

Resources either provide supplemental information or help users perform due diligence (via third-party certification, tools, technologies, etc). The following key indicates relevance to each of the four guiding principles.

KEY:

Author, Name  Define

Define  Level-Set

Level-Set  Engage

Engage

Description

Certification  See Certification Review

See Certification Review

Forest Management:

American Tree Farm System (ATFS)

Canadian Standards Association (CSA)

Forest Stewardship Council (FSC)

Sustainable Forest Initiative (SFI)

Wood Procurement:

FSC Controlled Wood

SFI Fiber Sourcing

SFI Certified Sourcing

Chain of Custody (CoC):

Forest Stewardship Council (FSC)

Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification (PEFC)

Sustainable Forest Initiative (SFI)

ASTM International, ASTM D7612 – 10(2015)

Standard practice for categorizing wood and wood-based products according to their fiber sources

ISO, ISO 38200:2018

Specifies requirements for a chain of custody (CoC) of wood and wood-based products

MetaFore (acquired by GreenBlue in 2009), The Fiber Cycle (2006).

These documents speak to how wood and fiber is managed, utilized, recovered and recycled in Canada and the United States.

NCASI, Update to the Fiber Cycle Technical Document

In this document, 2016 and 2017 data is used to update the original Fiber Cycle Technical Document results.

Proforests, Proforests.

Non-profit group that supports companies, governments and other organizations to implement their commitments to the responsible production and sourcing of agricultural commodities and forest products.

SPC, The Goals Database

A curated compendium of industry commitments aimed at improving packaging sustainability. Discover trends, analyze goals, and learn which topics have the most momentum in the world of sustainable packaging. This database is exclusively for SPC members.

United Nations (UN), Sustainable Development Goals.

Serve as a blueprint to achieve a better and more sustainable future for all. SDGs address the global challenges we face, including poverty, inequality, climate change, environmental degradation, peace, and justice.

United Nations’s FAO, The State of Forests 2020.

Reports on the status of forests, recent major policy and institutional developments and key issues concerning the forest sector. It makes current, reliable, and policy-relevant information widely available to facilitate informed discussion and decision-making with regard to the world’s forests.

WRI & WBCSD, Sustainable Procurement of Forest Products.

Provides simple, clear information about the 10 key issues related to sustainable procurement of wood and paper-based products. The guide is designed as an information support tool to assist users as they develop and implement their own procurement policies for forest products.

WWF, Responsible sourcing of forest products: The business case for retailers.

This report sets out to understand the business case for retailers to commit to and act on responsible sourcing of forest products, and shows that retailers see a clear link between responsible sourcing and business opportunities.

WWF’s GFTN, Guide to Legal and Responsible Sourcing.

Outlines the various ways in which sourcing organizations can exercise due diligence and demonstrate compliance with best practice based on compliance with their own sourcing policies.

Sedex, Sedex.

Provide practical tools, services and a community network to help companies improve their responsible and sustainable business practices, and source responsibly.

Transparency International, Corruption Perceptions Index

The CPI scores and ranks countries/territories based on how corrupt a country’s public sector is perceived to be by experts and business executives. It is a composite index, a combination of 13 surveys and assessments of corruption, collected by a variety of reputable institutions.

United Nations’s FAO, Traceability: A Management Tool For Enterprises and Governments.

Provides a thorough review of traceability. Outlines the vital factors to be taken into account when designing a successful traceability system, and explains the importance of made-to-measure systems in different contexts.

WRI, Forest Legality Initiative Risk Tool.

Provides forest products and legality information by country and by species.

WWF’s GFTN, Global Timber Tracking Network (GFTN).

Promotes the operationalization of innovative tools for species identification and for determining the geographic origin of wood to verify trade claims.

WWF’s GFTN, Keep it Legal.

This manual was developed to add detail to legality issues encountered by companies adopting a responsible purchasing program.

N/A, Timber Identification

Use of scientific and/or forensic methodology to confirm or disprove wood fiber origin and/or species declarations (through DNA analysis, wood fiber testing, near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS), etc.).

Chatham House, Forest Governance and Legality.

Monitoring forest governance and legality in 19 countries to assess the effectiveness of government and private sector efforts to tackle illegal logging and trade.

CITES of Wild Fauna and Flora, CITES Appendices.

Aims to ensure that international trade in specimens of wild animals and plants does not threaten their survival. Appendices I, II, and III to the Convention are lists of species afforded different levels or types of protection from over-exploitation.

FSC, FSC National Risk Assessment (NRA)

Provides a risk designation and assessment of the contiguous United States for the FSC controlled wood category.

ILO, ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work.

The Declaration commits Member States to respect and promote principles and rights in four categories, whether or not they have ratified the relevant Conventions. These categories are: freedom of association and the effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining, the elimination of forced or compulsory labour, the abolition of child labour and the elimination of discrimination in respect of employment and occupation.

ILO, Labor Standards.

The ILO has maintained and developed a system of international labour standards aimed at promoting opportunities for women and men to obtain decent and productive work, in conditions of freedom, equity, security and dignity.

Preferred by Nature (formally NepCon), Timber Sourcing Hub.

Provides information on risks of illegality by country. The score is based on our assessment of the risk of illegality occurring in 21 areas of law relevant to timber legality.

Earthworm Foundation (formerly The Forest Trust), Earthworm.

A non-profit organization built on values and driven by the desire to positively impact the relationship between people and nature.

Earthworm Foundation (formerly The Forest Trust), Starling

Starling combines cutting-edge monitoring technology with in-house expertise and market knowledge to allow users to take action and to drive change. Uses satellite imagery to help companies monitor and curb deforestation.

Global Traceability Solutions GmbH, RADIX Tree

Offers one solution for connecting and sharing data with your supply chain. Flexible tools provide visibility into the raw materials that make up products, help demonstrate compliance and mitigate risk.

SPC & AFF, Forests in Focus (FF)

A US based tool that helps members assess risks in the landscapes surrounding their new fiber mills, identify critical ecological needs in those areas, and make measurable conservation impacts on the ground (See dedicated section, p. 15).

WRI, Global Forest Watch.

An open-source web application to monitor global forests in near real-time.

*This is not an exhaustive list. The mention of specific companies, documents, or tools does not imply endorsement by GreenBlue, or a preference over other similar resources not mentioned. Descriptions were taken directly from the source whenever possible.

Suppliers / Manufacturers

Suppliers / Manufacturers

Assess and report on progress towards goals. Identify opportunities for improvement. Adjust strategies accordingly.

Assess and report on progress towards goals. Identify opportunities for improvement. Adjust strategies accordingly.